A Gong Show Disguised as a Baseball Team

Cosell’s rants aimed at Stengel and the Mets were the “first real mark” he made as a broadcaster. He blasted Stengel and the team early and often.

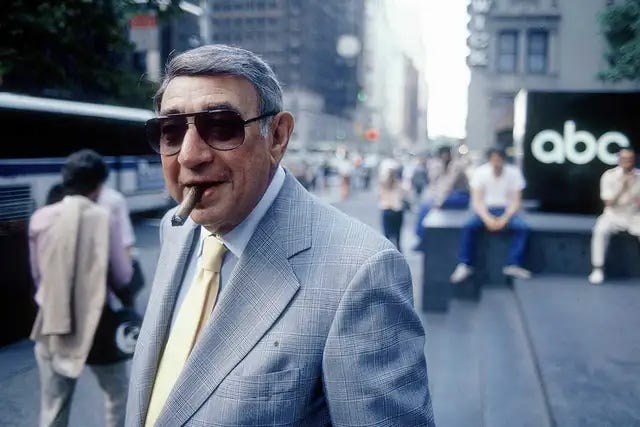

Howard William Cohen was labeled by peers, sports fans – even some allies – as arrogant, pompous, obnoxious, vain, cruel, verbose and a show-off.

Cohen, known better as Howard Cosell, agreed with every one of those infamous personal adjectives. In fact, Cosell embraced the name-calling and coveted the attention, for better or worse. The more emotional viewers would get, the more Cosell felt reassured he was doing his job.

It’s a job description few others wanted. Cosell enjoyed touching a nerve. He knew sports fans were passionate and it didn’t take much prodding to ignite the masses.

In his book, Howard Cosell – The Man, The Myth and the Transformation of American Sports, author Mark Ribowsky wrote:

Cosell was never boring or ignored … (he) made sports-watching not merely routine, but daring.

In 1962, Cosell’s employer WABC radio agreed to air the New York Mets pre and post-game shows. The deal was in place for two seasons when the expansion Mets played at the Polo Grounds under New York baseball legend Casey Stengel.

You’d have thought the collision of characters – Cosell and Casey – would have made for great folly, but the 1962 Mets were “a gong show disguised as a baseball team” wrote Ribowsky, a concept Cosell judged “a desecration unworthy of New York.”

Cosell was not amused by the antics of Stengel, Marv Thronberry or the 120 losses the team piled up in its first season. He knew he was under contract by WABC, not the New York Mets. The agreement allowed Cosell to rage against the machine.

According to Ribowsky, Cosell’s rants aimed at Stengel and the Mets were the “first real mark” he made as a broadcaster. He blasted Stengel early and often, claiming the bane of the Mets failure was rooted in “the pitiful example the old man (Stengel) was setting for a new generation of New York baseball fans.”

In an interview with Sports Illustrated reporter Myron Cope, Cosell said Stengel encouraged the Mets to “fall in love with futility,” using the media to ridicule players by name, deflating their confidence and turning them into punchlines.

“The sportswriters loved (Casey) Stengel because he gave them copy every day,” Cosell told Playboy. “What we soon had in New York was a press that celebrated futility, creating a legend out of almost purposeful futility.”

Cosell, sensing the opportunity to leverage his inflated self-import told Sports Illustrated, said he set off to “personally reshape the future of the Mets,” adding, “… “I went to work on getting rid of (George) Weiss … I poured it on.”

By the time the interview was published in March 1967, Weiss and Stengel were both gone, but as much as Cosell would like us to believe he was responsible for “reshaping” the Mets, the truth is the laughing stopped the day Tom Seaver arrived.

“Some people, who watched the Mets stumble through their first five seasons cracked jokes,” said Seaver. “I didn’t laugh. I wasn’t brought up on the Met legend; I wasn’t part of that losing history. I never did find defeat particularly amusing.”

Seaver immediately peeling away the layers of the “Lovable Losers” tag that Casey Stengel worked so hard to develop. Seaver, then a rookie, had no intention of falling in line as another happy-go-lucky loser. He led by example, winning 16 games in 1967, including Rookie of the Year and All-Star honors (his first of seven straight Midsummer Classic appearances). Then, of course, 1969, Seaver led the Mets, recording a 25-7 record and leading the Mets to a 100-win season and the team’s first World Series title.

I grew up watching the Mets and channel 7 Eyewitness News but had no idea that Howard Cosell was so opinionated on the Mets. I was very pro-Bouton kid at the time--taking glee in his ripping the band-aid off of pro sports at every opportunity--which put me diametrically against Howard on most issues. Cosell’s justified concern will now give me a new perspective on his legacy and legitimacy. It’s ironic that he may have overestimated his impact on their image makeover, yet a decade later another journalist, Dick Young, would be so key to its destruction.